COMMA at the Mc Master Museum of Art in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada.

Autoplasmic Exhibition 2011, curated by Michael Davidson.

Globe and Mail Review:

R.M. VAUGHAN

Special to The Globe and Mail

Published Friday, Apr. 15, 2011

"If, like me, you came of age in the transition period between paper-based and digital documentation, between physical records and binary-code-based information streams, you'll have a certain fondness for libraries and archives…" AutoPlasmic at McMaster Museum of Art Until May 28 at University Avenue and Sterling, Hamilton; www.mcmaster.ca/museum

If, like me, you came of age in the transition period between paper-based and digital documentation, between physical records and binary-code-based information streams, you'll have a certain fondness for libraries and archives, dusty shelves and curio cabinets. On a darker note, perhaps any system one relies on so heavily - digitalization, for instance - one automatically, wisely distrusts?

Artists are no less prone to such wary, self-preserving nostalgias.

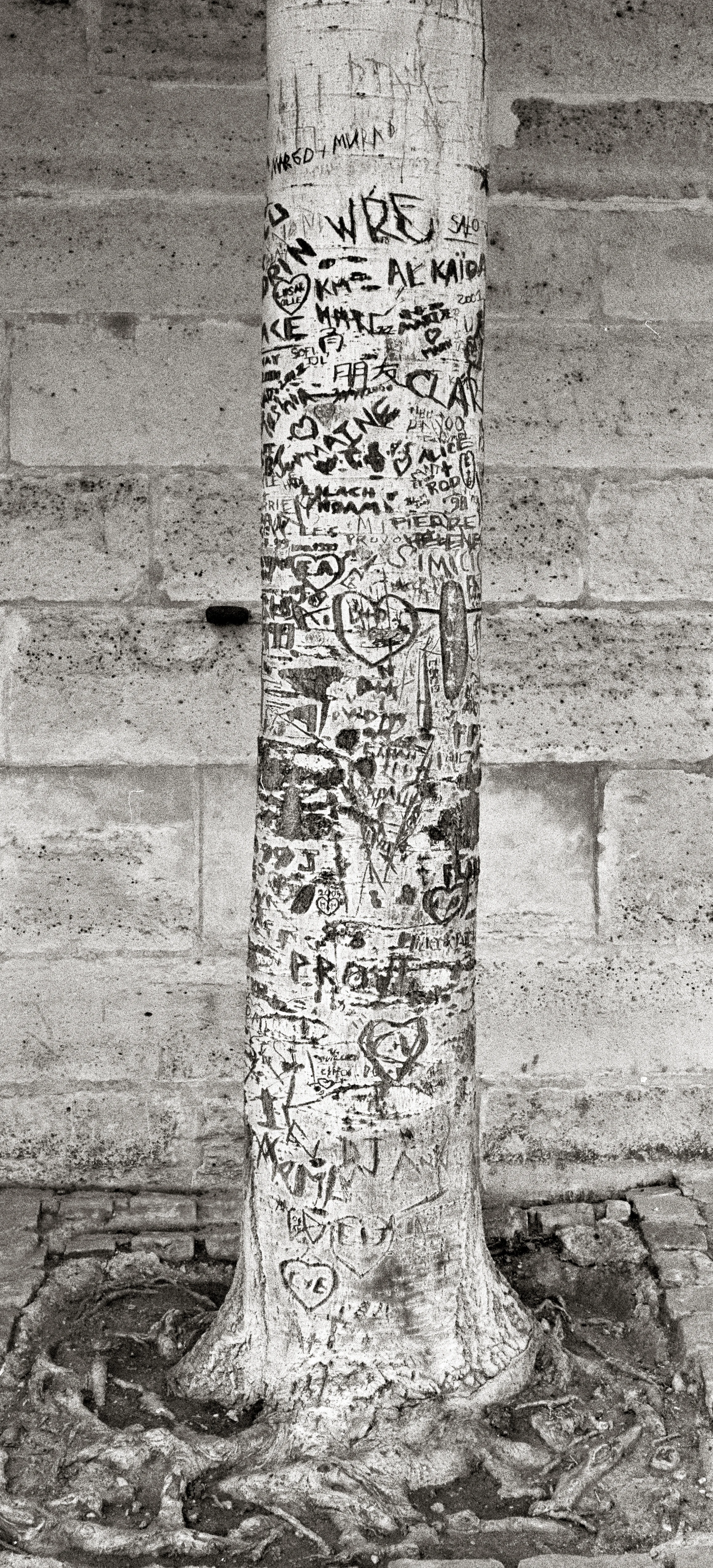

In the last year I've seen several shows that either replicated actual archives - the video collective Soft Turns's recreation of a library, in miniature, made from shredded books, Allyson Mitchell's AGO show featuring a hand-drawn replica of a lesbian archive - or employed archival techniques, the coveting of memorials and record-making, such as SAVAC's recent Monitor 7 video program, wherein works focusing on inventory keeping were highlighted, or Louise Noguchi's experimental documentary at Birch Libralato, a film that examined contested historical sites and the information they hold (and conceal).

A new group exhibition, AutoPlasmic, on view at McMaster University's Museum of Art employs the MMA's vast archival holdings to create a rich, textured and resonant show - one that uses a call-and-response scheme to connect historical works to contemporary practices.

The formula is simple enough: AutoPlasmic asks contemporary artists to dig through the MMA's vaults, find works they feel a kinship with, and then create response pieces. The results, however, are illuminating and multilayered, not only as peeks into the MMA's clearly substantial holdings (small museum does not equal small collection, in any sense), but also as illustrations of how artists perpetually, and must, create dialogue(s) with art history - that big pink elephant that lurks, sulks (and sometimes whispers good tips) in every artist's studio.

AutoPlasmic features current works by photo-based artists Michael Davidson, Jacques Oulé and Mario Scattoloni, each of whom has reacted, for lack of a better word, to everything from oils on canvas to sculpture and prints.

Davidson's mixed media on paper works are eerie near-photographs, a hybrid of print and photography that emphasizes stark, black-and-white contrasts and matches the resulting bald, scorched imagery with a weirdly complementary softness, a velvety, textured surface. His subject choices are primarily woodlands, haunted hallows and dilapidated buildings - all of which pair well, but not too obviously, with a ferocious, gory painting of a werewolf, by Don Van Vliet (a.k.a. musician Captain Beefheart), and an exquisite drypoint etching portrait of Victor Hugo by Auguste Rodin.

These mixes-and-matches are baffling, at first, until you realize that the landscapes and buildings Davidson spectrally recreates are, of course, the natural habitats of monstrous creatures or the ghosts of long-dead literary figures. That's a reductive connection, admittedly, but nevertheless the first step.

Further investigation into the pairings leads the viewer to see a connection between the familiar but removed, watery stasis (oxymoron intended) Davidson's occluded surfaces create and Van Vliet's twitchy, rabid and uncertain brushstrokes (so fresh they still appear wet), or Rodin's arguably unsympathetic tribute to Hugo, who is depicted as a shrouded, closed figure with a collapsing mask for a face and two opaque holes where his eyes should be.

Story continues below advertisement

Mario Scattoloni's brilliant, colour-drenched photographs of light-strafed interiors at night are less difficult to read in connection with his chosen complement - namely, a lovely, tiny Paul Klee watercolour that resembles a broken and haphazardly reconstructed church window.

Comprised of tumbling squares of diffused colour, the Klee is a perfect lapsed mirror to Scattolini's images, which break the night air into well-defined squares, halos and pockets of tangerine orange, indigo blue and river-grass green.

It helps, too, that Scattolini's works literally encircle the Klee painting, surrounding it like soldiers standing guard. If you care to read the didactics, you'll also learn that Scattolini's photographs were taken inside the lobbies of Barcelona homes, and that Klee's painting is subtitled "Spatial architecture, Tunisia" - thus, a Moorish connection. But you hardly need know that to appreciate this compelling dialogue between two butterfly collector-like appreciators of wandering colours.

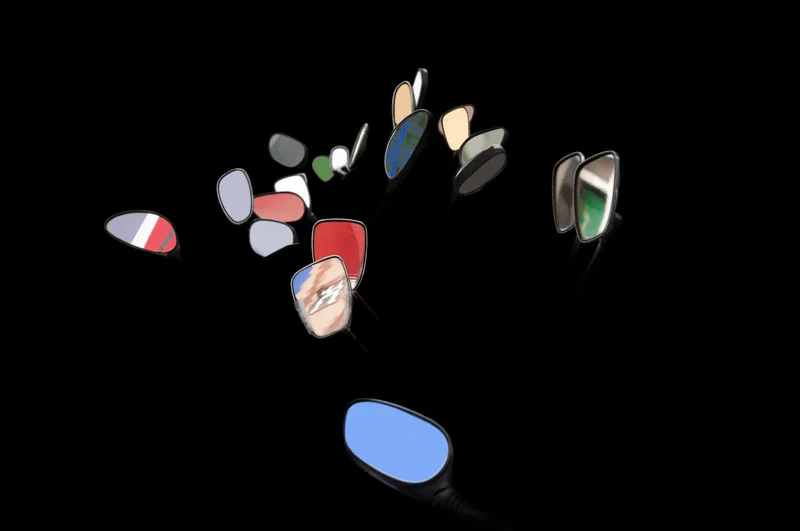

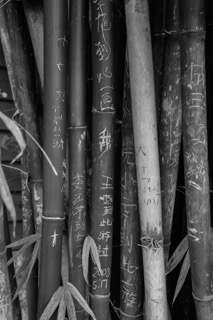

The standout sequence in AutoPlasmic is Jacques Oulé's response to Gerhard Richter's lustrous, pure pigment Mirror Painting ( Blood Red 736/6), a glassy square of, as the title alerts, hot, fresh-from-the-vein red.

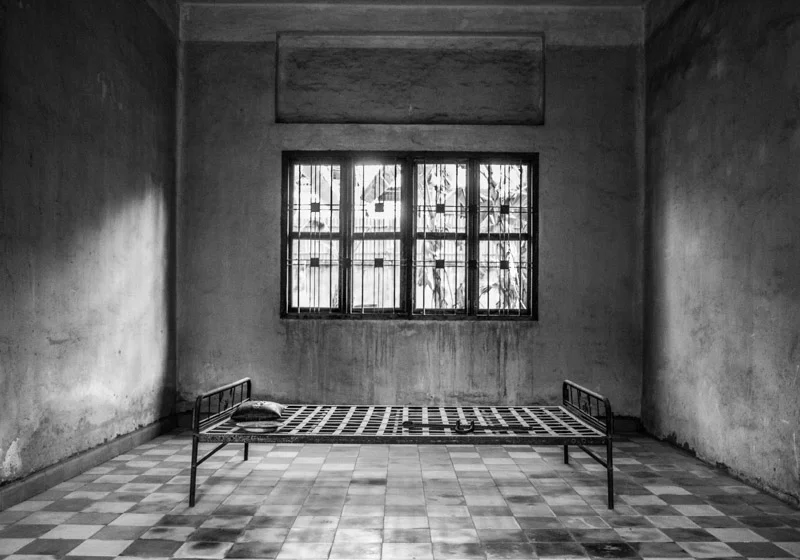

In two related series - one depicting the hand-painted room numbers found on a building once used as a killing depot by the Khmer Rouge, another capturing the heads and shoulders of a cluster of golden Buddha statues wrapped in a pinkish, reflective clear plastic - Oulé tackles the bluntness of Richter's painting head on, letting its unquestionable memetic power (who cannot relate to the colour of blood?) spin outward, reverberate across gallery walls, cultures and time.

The hand-painted numbers in Oulé's photos are humble, almost cute, and betray nothing of their carnage-strewn history. They are as opaque, in their innocuousness, as Richter's singular, unmitigated colour field. The Buddha statues, however, defy their wrappings, remain brilliant and authoritative even while shrouded in common packing materials, thus reflecting the other, counter quality of Richter's painting - its unrelenting, bossy shininess, its lit-from-the-inside gloss.

Blood red is the most primal of primary colours, and Oulé's photo-series investigate both its brute force and magisterial glamour, it's worst- and best-case connotations.

Truly ahistorical yet history-driven, AutoPlasmic is a contradictory sort of show. It prompts the viewer to circle and recircle the assembled works, to read the show backward and forward in order to make cross-historical connections - ephemeral and literal.

Wander, backtrack, repeat.